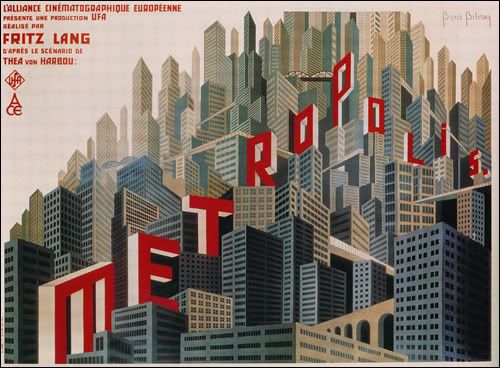

Fritz Lang, “Metropolis” (1927)

Picture source: www.tobatheinfilmicwaters.com

The version of “Metropolis” I saw recently is the restored and digitally remastered one done under the supervision of the Murnau Foundation in Germany with the addition of the original orchestral soundtrack composed by Gottfried Huppertz in 1927. This version was released on DVD in 2003 and is quite a long film at nearly 2 hours. Even then, there are still scenes missing from the restoration, scenes that were thought to be lost forever until a copy of the movie with nearly all the lost scenes turned up in the Museo del Cine in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 2008 and in turn was complemented by uncensored scenes found on a copy of the movie in the National Film Archive of New Zealand by an Australian researcher in 2005.

The plot may be a familiar one for those raised on H G Wells, Aldous Huxley and George Orwell’s science fiction novels by high school teachers: Metropolis is a mighty futuristic city designed and built by the scientist-ruler Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel) and its population is divided into an idle rich who enjoy the city’s bounty, and a majority oppressed poor who work at the machines that power the city and supply its wealth in shifts around the clock. The rich and the poor are kept strictly segregated, at least until Joh Fredersen’s son Freder (Gustav Frohlich) sees a beautiful young woman Maria (Brigitte Helm) barging into a pleasure garden with a bunch of dirty workers’ children. She and the littlies are hustled out by security guards but Freder is smitten and tries to follow her; he ends up stumbling into one of the colossal machine caverns and witnesses an accident that kills several people. Distressed, Freder reports the accident to his father and is horrified at Fredersen’s dismissal of a bureaucrat, Josaphat (Theodor Loos), for the accident. From this moment on, Freder determines to find Maria, help Josaphat get his job back and understand the work that the poor do and the conditions they work under, in order to relieve the workers’ oppression and poverty.

Fredersen sniffs something afoot with his son so he orders his spy, known as the Thin Man, to trail him and Josaphat. He also consults another scientist Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) who has been working on a pet vanity project, the Machine Man, based on Fredersen’s dead wife Hel whom Rotwang also loved. Fredersen and Rotwang visit the catacombs beneath Metropolis and discover Maria addressing a mass rally of workers about a mediator who will come and reconcile the workers and their rulers. Fredersen fears a workers revolt so he instructs Rotwang to use the Machine Man to disrupt Maria’s rallies. Rotwang agrees to do so: he kidnaps Maria and uses his technology to give Maria’s likeness to the robot, then sends the robot into the streets to create havoc in Metropolis while holding Maria hostage. It soon turns out Rotwang has hated Fredersen for a long time and wants to destroy him and his life’s work: Metropolis.

From now on, the film drops into an action thriller in which Freder performs amazing non-stop feats of athleticism: helping Maria, freed by Fredersen, to rescue the workers’ children from floods that engulf the city as a result of the workers’ sabotage of the machines; fighting off the workers who want to lynch Maria when they discover they have been tricked by the robot lookalike into destroying the machines; and rescuing Maria from a crazed Rotwang who kidnaps her again. The plot turns and twists a lot and goes into some by-ways which, though interesting in themselves, add little to the story and drag out Freder’s quest.

The sets created for the movie are austerely beautiful, streamlined and impressive with a style influenced by the Art Deco and Modernist architectural styles popular at the time. The cityscape backgrounds with buildings that look like cousins of the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building in New York City all bunched together and streams of cars and trains encased in tubes zooming from one structure to the next are still referred to by current science fiction movies like Alex Proyas’s 1998 film “Dark City” for influence. The design of the Machine Man does not look too dated – well, a few bolts taken off here and there and the robot would be pretty up-to-date – and when the thing moves, it still sends chills up and down the spine.

Some sequences are worth mentioning: Freder’s “Moloch!” impression of the machine in meltdown, swallowing up workers, and the machine itself transforming into a demonic devourer of human sacrifices; Rotwang’s complicated transformation of the Machine Man into the false Maria with circular rays moving up and down its body while lightning flows between it and the real Maria, bolted down in a giant test-tube contraption; the tale of Babel as interpreted by Maria with shots, looking towards the style of Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda documentaries for Nazi Germany, of the Babel tower and the hundreds of slaves required to build it; the robot Maria in the Yoshiwara entertainment district, dancing frenziedly and seductively before the slavering, lustful male elite who are shown as all eyes; and a frightening dream sequence in “Intermezzo” in which statues of the Grim Reaper and skeletons swathed in toga-like garments come alive and play instruments. In these scenes, the special effects can be something to behold and the montage of images leave a very strong impression of suffering and oppression in the Babel tower scenes, and of the sensual banality of the lives of the rich elite in the false Maria’s dancing scenes.

For all the film’s stylistic achievements, the plot itself is treated superficially with a trite conclusion: the workers’ conditions are so harsh and their revolt is so intense and Fredersen himself is so steeled against the workers’ interests that when he and the workers’ leader Grot (Heinrich George) meet as equals, the resolution of their meeting is a mawkish cop-out. You know any reconciliation between the rich and the poor, even though engineered by Maria and Freder, is likely to be short-lived and once Metropolis is up and running again, the old problems of rich-versus-poor will be too great for Freder, Josaphat and Maria to mitigate and resolve. For one thing, the poor are depicted in the movie as ignorant, easily led by populist leaders, propaganda and religious mumbo-jumbo, and prone to violence; and the rich are equally dumb and obsessed only with immediate sensual gratification. How two social classes concerned only with immediate security and unfamiliar with political, social and economic co-operation can be persuaded to give up some or most of their own interests in order to live and work peacefully together in a new social and economic system where all are equals is a project requiring much education, negotiation, compromise and in particular open democracy, a condition no-one seems to know about in Metropolis.

Incidentally “Metropolis” script-writer Thea von Harbou, married to Lang at the time, mustn’t have known or understood much about democracy herself – to be fair, few people in Germany in the 1920’s did, seeing the Weimar Republic and democracy as something imposed by foreign enemies after the country’s defeat in the Great War of 1914-1918 – as years later, divorced from Lang, she wrote the script for the movie “Der Herrscher” (1937) which advocates absolute and unquestioning submission to the Nazi German state and to the Fuhrer in particular.

The musical soundtrack also lets the film down: one surely would have thought that a futuristic film would require a futuristic-sounding music score using the latest advances in music technology and composition at the time. The theremin, the world’s first electronic musical instrument, had been invented in the Soviet Union in 1920 and had been toured throughout Europe for several years already so it’s a puzzle as to why Lang elected to go with a conventional orchestral music soundtrack using traditional forms of composition.

The acting can be very over-the-top – witness Maria recoiling from and trying to escape Rotwang in the catacombs, she appears to be having one spasm after another – but acting histrionics are pretty much par for the course in silent films: how else can actors get across extreme emotion if audiences can’t hear them scream or sob?

There is a running motif of religion in “Metropolis”: Maria is a forerunner of Metropolis’s supposed saviour; and she and the robot doppelganger might be seen as a Christ / Anti-Christ pair as well as the traditional Madonna / whore couple beloved of traditional forms of Christianity. Monks and images of death appear in Freder’s dream in the “Intermezzo” sequence. Apparently Lang wanted to include even more religious imagery and allusions to religion in “Metropolis” but von Harbou balked at including any more religion in the film. I’d have to agree as the film at 120 minutes is already very long and has more than its fair share of cultural references and plot sidelines.

Still with a number of powerful sequences such as those mentioned earlier, the incredible images of the city and the Machine Man, and the theme of how different social classes and their interests and concerns might be reconciled, the film deserves its iconic status as trend-setter for future science fiction dystopian visions to follow: one such film incidentally is a remake to be produced by German producer Thomas Schuehly.